Investigación

Cultural practices for the care of indigenous pregnant women of the Zenu Reserve Cordoba, Colombia

Prácticas culturales de cuidado de gestantes indígenas del Resguardo Zenú Córdoba, Colombia

Práticas culturais do cuidado de gestantes indígenas do assentamento Zenú Córdoba, Colômbia

Claudia Patricia Ramos-Lafont*

Irina Maudith Campos-Casarrubia**

Javier Alonso Bula-Romero***

Abstract

Objective: Describe t he culture care practices of pregnant indigenous women that live in the Zenu reserve located in the savannah of Cordoba, Colombia. Materials and methods: Qualitative, ethnographic focus supported by the ideas of Colliere and Leininger. 10 pregnant indigenous women were interviewed, until reaching theoretical saturation. The cultural knowledge and taxonomic analysis allowed to perform a composed analysis in which the following subjects were compared, classified and grouped: Being pregnant for the Zenu women; taking care of themselves during pregnancy: a guarantee for the unborn child; the coldness and its consequences, the midwife as a control and care character of the Zenu woman during pregnancy and birth. Result: The Zenu woman begins prenatal care, as soon as she identifies her pregnancy, through some proper pregnancy characteristics that are accurate for them. Once the pregnancy is identified, a series of care practices begin, including eating well, avoiding heavy duties, caressing the belly with the midwife, bathing early to avoid coldness and avoiding sexual relationships to prevent malformations. Conclusion: The Zenu woman has its own pregnancy care practices and ways of protecting the unborn child, besides trusting the care and attention brought by the midwifes. The nursing care offered to these women must be done based on the transcultural knowledge proposed by Leininger.

Keywords: Nursing, transcultural nursing, culture care, traditional medicine.

Resumen

Objetivo: Describir las prácticas culturales de cuidado de mujeres indígenas grávidas que viven en el resguardo Zenú ubicado en la sabana de Córdoba. Materiales y métodos: Enfoque cualitativo, etnográfico sustentado en las idea s de Colliere y Leininger. Fueron entrevistadas 10 gestantes indígenas, hasta alcanzar la saturación teórica. Los dominios culturales y el análisis taxonómico de ellos permitió realizar un análisis componencial en el cual se contrastaron, clasificaron y agruparon las siguientes categorías temáticas: Estar embarazada para la mujer zenú; cuidarse durante el embarazo: una garantía para la protección de su hijo por nacer; la frialdad y sus consecuencias, la comadrona como personaje de control y atención de la mujer zenú durante el embarazo y el parto. Resultado: La mujer zenú empieza su cuidado, tan pronto identifica su embarazo, mediante unas características propias del estado que son fiables para ellas. Una vez es identificado el embarazo, se inician una serie de prácticas de cuidado entre las que sobresalen el alimentarse bien, evitar hacer oficios pesados, sobarse la barriga con la comadrona, bañarse temprano para evitar la aparición de la frialdad y evitar tener relaciones sexuales con el fin de prevenir malformaciones en el hijo por nacer. Conclusión: La mujer zenú tiene sus propios modos de cuidar su embarazo y proteger a su hijo por nacer, además de confiar en los cuidados y la atención que le brindan las comadronas. El cuidado de enfermería que se ofrece a estas mujeres debe hacerse con base al conocimiento de la enfermería transcultural propuesto por Leininger.

Palabras claves: Enfermería, etnoenfermería, cuidado cultural, medicina tradicional.

Resumo

Objetivo: Descrever as práticas culturais do cuidado de mulheres indígenas grávidas moradoras no assentamento Zenú localizado na savana de Córdoba. Materiais e métodos: Caráter qualitativa, etnográfica baseada nos postulados de Colliere e Leininger. Foram entrevistadas 10 gestantes indígenas, até a saturação teórica. Os domínios culturais e a sua análise taxonômica permitiu realizar uma análise de componentes na qual contrastaram-se, classificaram-se e agruparam-se as categorias temáticas: “Estar grávida para a mulher Zenú”, “cuidar-se durante a gravidez: garantia da proteção do filho por nascer”, “A friagem as suas consequências”, “A parteira como personagem do controle e atenção da mulher Zenú durante a gravidez e o parto”. Resultados: A mulher Zenú começa os seus cuidados no momento que identifica seu estado de gravidez, confirmação feita por características que são definidoras para elas. Começam uma série de rituais de cuidado entre as que se destacam a boa alimentação, restringir ofícios pesados, fazer massagem na barriga pela obstetriz, tomar banho cedo para evitar a friagem e restringir-se de relações sexuais para prevenir malformações congênitas no filho que está por nascer. Conclusão: A mulher Zenú tem os seus próprios rituais de cuidar a sua gravidez e proteger o seu filho por nascer, além de ter os cuidados e a atenção das parteiras. O cuidado de enfermagem que se presta a estas mulheres deve ser feito baseado em conhecimentos da enfermagem transcultural postulada por Leininger.

Palavras-chave: Enfermagem, etnologia, cultura indígena, medicina tradicional.

Introduction

The Zenu population was discovered by Alonzo de Ojeda in 1515. At that moment, it was a declining urban center due to the first attack of the Spanish, according to Bello and Paternina (1, 2). The Zenu were organized in a cacicazgo (lands ruled by a cacique), a society stratified in three big groups: farmers, fishermen, and artisans, who exchanged products; they had not developed military and had urban centers which other small villages depended on (3).

The pregnant indigenous women, as members of the community, must abide the law and follow the regular conducts. For the pregnant Zenu women to participate in the study and share their traditions, and also allowing recordings and/ or photographs, its necessary to have the explicit authorization from the cazique, which is given to the community through a minor captain in the cabildo. According to their laws, the pregnant women and the general community have no autonomy to decide on their participation on studies, researches or any other inherent aspects to the community; most women are analphabets and its considered that it is not necessary nor convenient for women to attend school, a privilege that is reserved just for some men (4). The Zenu community declare that the equilibrium between physical well-being and the harmony of a healthy soul is achieved through a respectful interrelation between the occidental knowledge and the ancestral knowledge. Thus, traditional medicine is a fundamental component that cannot be ignored (2, 5).

Culture refers to the inclusion of knowledge, beliefs art, morality, laws, traditions and any other skill o r custom that humans acquire when they are members of society (6). The doctor Madeleine Leininger (1978) defines culture as the knowledge acquired and transmitted about values, beliefs, behavioral rules and life style practices, that structurally orientate a determined group in their thoughts and activities. This researcher determined that it was of vital importance for nursing personnel to consider the cultural dimension when providing care (7).

Regular care is based on all kinds of customs, traditions and beliefs. As the life of a group consolidates, a whole ritual arises, a culture that programs and determines what is considered good or bad to preserve life. These cares represent the weave of life, as well as securing its permanence and duration. As a result of the application between anthropology and nursing the cultural dimension emerges in nursing care. Its relevance consists on the information given by the individuals about their cultural values and the world view of a particular group. Therefore, Leininger sustains that transcultural nursing are all actions and decisions of aid, support, facilitation or training that cognitively adjust to the cultural values, beliefs and lifestyle of the individuals, groups or institutions with the purpose of supplying or support welfare services or health care that are significant, beneficial and satisfactory (6, 7); that also promote, the study about culture care to find new and different ways of serving people from diverse cultures. The researcher is emphatic on inviting nurses to discover the diversity and universality of care around the world.

In what refers to the care of the expecting mother, it is intended to improve the life quality of the mother and the unborn child. For that purpose, the participation of the expecting mother and her family is fundamental, and it should be considered that the care practices vary from one culture to another and also during different chronological times (6). Some inconveniences have arisen in the communities regarding maternal and perinatal care consequence of the changes in culture care traditions to include new practices coming from outside or from other cultures (colonization). This situation has generated cultural conflict and has moved the traditional mode on how people satisfied their needs and maintained harmony with the environment, as a result of the many changes in care practices for pregnant women and the newborn baby, specially in the diet and the family structure (1).

The care practices of the pregnant women are the result of realization of domains, getting ready for the birth of their baby and having the appropriate eating practices. When these are analyzed, it allows to see how they are implemented during pregnancy and how they contribute to the physical and emotional wellbeing of the mother and the unborn child. Also, it established that its determination have more weight than the recommendations given by professional, because, they consider the child more important than the mother-baby dyad.

As a consequence, research recommends that for professional nursing training its necessary to strengthen communication abilities, this way directing educational practices towards comprehension of social and intercultural relations of pregnant women, this suggests a review of the curricular contents related to this aspect.

It is evident that the production of knowledge contributes to the culture care for maternity at different times, but its necessary to advance this knowledge in the different community groups and indigenous populations. Therefore, the following research question was contemplated: What are the culture care practices for indigenous pregnant women at the Zenu reserve, located in the savannah of Cordoba, Colombia?

Given that the purpose of the maternal and perinatal care pathway from the Ministry of Health and Social Protection (Resolution 3202/2016) is to contribute to the promotion of health and the improvement of maternal and perinatal results, through comprehensive health care -including the coordinated and effective action of the State, the society and the family about the social and environment determinants of the health inequities-and that within the collective interventions the strengthening of bonds must be guaranteed to reinforce social support not only from family and community members but also from institutions, in order to create or strengthen maternity homes and the articulation of traditional medicine agents -such as midwifes- to the health system. This results in the need of understanding that culture has a solemn meaning in social groups and possesses an ancestral force; from this the importance of returning to care by means of communication processes between the health personnel and expecting indigenous mothers.

Objective

Describe the culture care practices of indigenous pregnant women that live in the Zenu Reserve, located in the Savannah of Cordoba, Colombia.

Materials y Methods

An ethnographic, qualitative research was proposed, based on the ethno-nursing focus proposed by Madeleine Leininger in 1991 (8). This research worked on the emic approach, from the group of pregnant indigenous women perspective on beliefs about care practices, which reflects experiences, beliefs and language from their culture.

The study attempted to establish what are the perspectives that are used to understand and see the different realities that form the order of human societies, as well as learning the logic of the paths that are built to produce -intentionally and methodicallyknowledge about them (9). Similarly, the quality of the activities, relationships, issues, means, materials and instruments in a determined situation or problem were addressed, with the purpose of reaching a holistic description where the particular issue or activity is exhaustively analyzed, in this case the care practices of pregnant indigenous. Differing from the descriptive, correlational or experimental studies, more than determining a relation of cause and effect between two or more variables, the qualitative research is interested in understanding how dynamics occur or how the process of the issue happens (10).

A total of 10 indigenous pregnant women participated, with chronologic age between 22 and 35 years, multiparous, with gestational age among the second trimester of pregnancy. For the recollection of information, the procedures from the ethnographic interview proposed by Spradley were followed (11) and an immersion in the reserve was performed with the purpose of understanding the cultural scenario, lifestyle, social relations and their environment (12).

The interviews were recorded, with previous authorization from the participants, and then transcribed textually, guaranteeing that the analyzed data were a genuine copy of the expressions from the pregnant indigenous.

Once the cultural domains were identified, a taxonomic analysis was performed with the obtained data. At this stage the information content was studied, identifying all the symbols of a domain, finding subsets of symbols and existent relations between the subsets (13), with the purpose of having a wider perspective and finding relations between the domains to obtain a picture of the culture care practices of the pregnant women from the Zenu reserve.

This study is qualified as low risk, according to the Resolution 008430 of 1993 of the Ministry of Health a nd Social Protection. The expecting mothers that accepted to participate were informed about the objectives of the research, approving their participation by signing an informed consent. The study had the approval from the regional cacique in Cordoba- Sucre to perform the research in the Zenu reserve. The study also counts with the approval of the Research Ethics Committee from the National University of Colombia.

Results

The culture care practices identified in the Zenu expecting mothers show a great influence from their community cultural traditions and customs, a phenomenon that highlights the importance of culture care and culture, as defined by Leininger in her theory (14). For Zenu women, the protection they provide to the baby through care is of extreme importance and reliability, as well as the care provided by the midwifes of the community, which contrasts the etic care provided by the EPS-i (Colombian Health Care Facilities for Indigenous).

The Zenu woman begins care as soon as she identifies her pregnancy, with the appearance of some proper char acteristics of pregnancy that are reliable to them. Once pregnancy is identified, a series of care practices begin, standing out eating well to have enough blood and for the baby to be born healthy, avoiding heavy duties to prevent miscarriage and premature birth and, as consequence, the death of the baby; caressing the belly with the midwife to keep the baby well positioned and to avoid complications, showering early to avoid coldness along with its consequences and avoiding sexual relationships to prevent malformations.

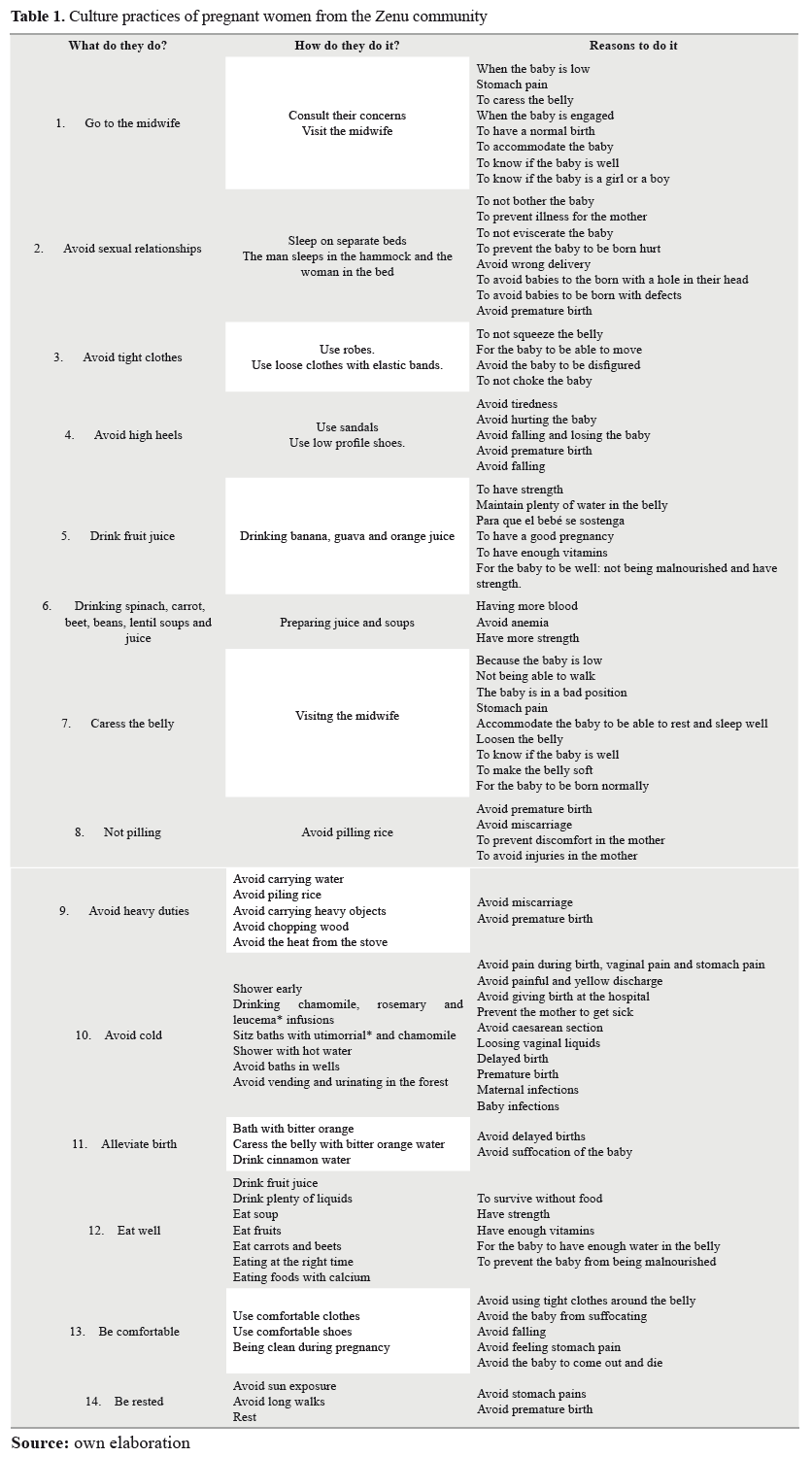

Avoiding coldness and its consequences is an important act of protection for the Zenu woman, given that preventing coldness impede the majority of complications that can unfold during pregnancy and protec ting the baby from diseases and even death. Visiting the midwife monthly or when felling discomfort is an act of reliability of the pregnant Zenu women toward these community women, who have inherited the knowledge of emic care from their ancestors, in a way that they can control the pregnancy and birth of the expecting Zenu mothers. Generally, it can be said that culture practices performed by pregnant women from the Zenu community can be synthesized by what they do, how they do it and the reasons to do it, as presented in the following table:

Description of the thematic categories

• Being pregnant for Zenu women

When a woman is expecting, she can perceive a series of suggestive signs and symptoms and their magnitude varies in each mother. A late period is an important sign, as well as nasal congestion, augmented breast sensibility, tiredness, nausea and vomit, which generally happen in the morning and are directly related to an increased level of progesterone and human chorionic gonadotropin (15). Other symptoms are associated with a higher perception of odors, appetite or repulsion to some foods as consequence of sensory changes, dizziness and faints that emerge due to low blood pressure. These are the most frequent signs and usually appear during the first trimester, particularly on the first pregnancy.

“i knew that i was pregnant because i got dizzy, i wanted to vomit, i was sleepy and lazy. i had all these symptoms and my companion told me that i was pregnant, and i told him no. Since i didn´t get my period ended up being pregnant”. 23-year-old expecting Zenu mother.

“i knew that i was pregnant because i got dizzy, i had vomit, stomachache, headache, and food made me nauseous”. 23 -year-old expecting Zenu mother.

“Well, i knew because i got dizzy often, i wanted to vomit and also i felt sick when i saw food and i couldn´t eat”. 25-year-old expecting Zenu mother.

For the Zenu women, the absence of their period (menstruation), general malaise, vomit, dizziness, disgust, hypersalivation, not being able to hold food in the stomach, not being able to eat, headache, cramps and somnolence are the most common characteristics for pregnancy in the community.

• Pregnancy care: a guarantee for the protection of the unborn child

For indigenous pregnant women from the Zenu community, pregnancy care is important, and they know well their practices, which have been taught through generations (mothers, grandmothers, mother-in-law).

“She tells me that and explains to me and then i do it because she tells me, then i ask her the reason to do it and she tells me that coldness affects you and certainly and she also tells me that i can’t shower at night; she scolds me because i can’t shower in the afternoon, i have to shower early so that i don’t get wet at night”. 24-year-old expecting Zenu mother

Avoiding heavy duties such as carrying big or voluminous objects, piling rice, chopping wood or carrying water can prevent miscarriage and premature birth. These actions coincide with the prevention methods established in the guide or early detection of pregnancy complications from the Ministry of Health and Social Protection, where risk factors of pregnancy such as occupation, physical effort and work schedule are prominent.

“Well, the activities that i do here don’t require much effort, for example, carrying a gallon of water. But that’s bad because you’re at risk of losing the baby because of lifting heavy stuff”.21-year-old expecting Zenu mother

For them, it is also important to rest frequently during the day, not getting too much sun exposure and avoiding long walks, these can cause premature birth which implies resorting to health institutions (hospitals and clinics) for their baby to be born and a high probability of needing a caesarean section, something that is not pleasant, according to their customs, since their beliefs require giving vaginal delivery and the fact of having a caesarean section reduces their strength as women.

“See, what happens is that my mom says that when you pile, the head of the baby feels the beats and the baby can come out.”23-year-old expecting Zenu mother

Expectant indigenous agree to prenatal care visits and receive the correspondent medical exams, but not to hospital maternity services. They prefer to give birth in their homes, with the midwife, maintaining good prenatal care practices to avoid going to a hospital and having a caesarean section. EPS-i work with the midwifes from the community to reduce the risk of complications during birth (16).

• Coldness and its consequences: a pregnancy risk for the expectant Zenu

One of the main problems referred by the women in the study and that, according to them, can occur is coldness, which is defined as a condition that appears when the necessary care fails, mainly when they are not careful about showering with cold water and late in the day, the reason is cold can enter through the genitalia and it has consequences both for the mother and the baby.

Within the consequences of cold from the mother are the pains in the uterus and genitals, more pain during birth and yellow discharge that cause malaise and stomach pains. Among the consequences that coldness can bring for the mother are pain in the uterus and genitals, increased pain during labor and the appearance of yellow discharge that cause discomfort and stomach pain. The appearance of coldness, according to the indigenous, is related to caesarean births, sick and hospitalized newborns, the loss of amniotic liquids, prolonged labor, premature births and a series of infections in the mother and the newborn.

Expecting mothers in the Zenu community attribute coldness to the main complications that occur during pregnancy, mainly those associated to the appearance of vaginal discharge; however, it was found within the professional systems that during pregnancy, increased vaginal discharge occurs as a consequence of higher levels of hormones in the placenta and that it is a whitish, odorless discharge, similar to premenstrual discharge. If the discharge is of yellow or green color, thick, with a strong odor, also with symptoms like itchiness, burning or irritation in the genital area, it can be an infection caused by different bacteria, which needs a specific and rapid treatment to prevent harmful consequences for the pregnancy and birth of the baby.

There are maternal and fetal causes that can impede the normal labor. If any of these causes appears, its necessary to perform a selective or emergency caesarean section to save the life of the mother and the baby (17).

The cultural belief of the Zenu community about coldness as a cause of complications during pregnancy and birth is part of the popular or generic systems which have to be negotiated for culture care. If there are enough arguments within the nursing care and professional systems that indicate the true causes of these complications and is evidenced that the expectant mothers of the Zenu community do not have enough care practices to prevent them -although the culture care practice of avoiding coldness is not harmful for them- other nursing care practices that are coherent to their culture and that also generate health and welfare have to be negotiated.

“Yes, another thing my mom says is that i can’t shower late at night, that i can shower at 12, because if you’re pregnant and you shower late, it affects the baby and it makes you sick; yes, if you get coldness the baby comes out sick and they tell me that labor can come in earlier, that i get the urge of giving birth earlier and that baby can’t be born, because coldness won’t let the baby to come out”. 21-year-old expecting Zenu mother.

“Look, i shower in the morning and also at midday like at 1 and after that i don’t shower anymore, because you get cold inside; when you’re cold inside that makes you feel a lot of pain when you’re in labor and you just let out the cold, but the baby can’t come out”. 23-year-old expecting Zenu mother.

The beliefs about coldness is a knowledge that has to be reoriented and restructured since in some occasions it can be harmful for the health of the expecting mother, and not being able to detect and correct the true causes of pregnancy complications in time implies not being able to prevent maternal and fetal consequences.

• The midwife as a character of control and attention for the Zenu women during pregnancy and birth

In the indigenous Zenu community, women receive their position as midwifes and are in charge of the care of pregnant women, although they have no professional education. These are elder women from the community which have received the legacy of their mothers and grandmothers to provide care for the expectant mothers, they count with great acceptance and credibility from the community, and for pregnant women, it is indispensable to consult them during pregnancy to be sure about the evolution of their pregnancy and the welfare of the baby.

The expectant mothers visit the midwife about once a month to know about their pregnancy, the welfare of the baby and to be sure of having a normal delivery (vaginal delivery). Also, they visit the midwifes in special occasions to “caress the belly” when feeling pain or when they feel the baby is engaged, with the purpose of accommodating the baby.

“i visit the midwife for her to check my belly and tell me the baby is well. When it hurts, i visit her so she can caress the belly and also when the baby feels low and i can’t walk well. Then, she caresses the belly and accommodates the baby and i feel better. She caresses the belly with oil and accommodates the baby so i can have a normal birth. i go every month, when feeling pain or when the baby is engaged here of there, then i visit her, and she caresses the belly and i feel better”.21-year-old expecting Zenu mother.

The culture care provided by the midwifes from the Zenu community is a fundamental part of their cultural origin, social structure and conception of the world. Therefore, care can not be separated from their culture, but it can be strengthened for a more beneficial care, in benefit of perinatal and maternal health in the community (18).

In the analyzed testimonies, the trust deposited to the midwifes of the Zenu community by the expectant mothers can be noticed: elder women from the same community that are not health professionals and do not count with professional instruction from an educational institution referring to the care of pregnant women, but do have ancestral knowledge, inherited from generations, from their mothers and grandmothers about what has traditionally been, pregnancy care for Zenu women (19, 20). This knowledge is supported and accepted by the community and is indispensable for the welfare of the expecting mother and the unborn baby; its susceptible of being strengthened by nursing knowledge, with the purpose of achieving greater welfare for the expecting mother and preserving the cultural origins.

Discussion

Care refers both to abstract phenomena and concrete situations. Leininger has defined care as those experiences or ideas of assisting, supporting and facilitating toward others with evident or anticipated health needs, to improve the human conditions or lifestyle (18). Care, as one of the main constructs of the Leininger theory, includes both the traditional and the professional, which have been expected to influence and explain health and welfare of diverse cultures (13).

Similarly, the researcher defines two important constructs within the transcultural care theory: the terms emic and etic. The term emic, refers to the knowledge and the local, indigenous or within a phenomenon cultural vision, while etic refers to the outside or strange vision of health professionals and the institutional knowledge of the phenomenon (21). Generic care (emic) refers to the practices and secular, indigenous, traditional or local knowledge to provide acts of assistance, support and facilitation for or toward others with evident or anticipated health needs, with the purpose of improving their welfare or help with their death or other human conditions (14).

Pregnant Zenu women have care and protection practices that are found within the generic or emic care defined in the transcultural care theory of Leininger, including diverse pregnancy care practices such as avoiding lifting heavy objects, piling rice, chopping wood or carrying water. These care practices, viewed from the expecting Zenu mother, contributes to not having a miscarriage and premature birth. Also, expecting mothers base their diet on fruits, fruit juice, soups and liquids during pregnancy, with the interest of having enough water in the womb (22).

Similarly, it is important for them to consume beans, lentils and spinach, foods that prevent anemia and favor the baby for being well nourished. Another fundamental and important action for Zenu women is to visit the midwife, since she has the generic knowledge for pregnancy care and assists the mother during pregnancy and birth, guaranteeing a normal pregnancy and a healthy baby.

The pregnant indigenous from the Zenu community, as an action of protection for their unborn baby, avoids sexual relationships, especially during the last pregnancy stage in order to avoid premature birth and the baby having malformations. This is a belief that has been accepted by men in the community, in benefit of the care of the mother and their babies (23). Also, as self-protection and for their babies, pregnant women shower early (before midday) in order to prevent coldness and its consequences, that go from pain and vaginal infections to premature birth and diseases in the newborn babies, an action that is complemented with the consumption of natural plant infusions.

According to Leininger, it is necessary that the nurse and the rest of the health team understand and learn about the generic care of human beings, with the objective of reaching an agreement from both parts, to offer a culturally congruent care, this way, avoiding belief conflicts and benefiting the welfare of the people that receive the care (24).

Care practices such as pregnancy checkups with the midwife could be negotiated or accommodated to guarantee the prevention of pregnancy complications and the restructuration or change of patterns of culture care, referring to professional actions and mutual decisions of assistance, support, or facilitation that can help people to reorganize, change, modify or adjust their lifestyle in institutions, to improve the health care patterns, practices or results (25, 26). The belief that coldness causes most pregnancy complications during pregnancy and labor is an apt situation to implement a change of the cultural patterns since showering early and avoiding coldness are not harmful for the expecting mothers (27, 28), but the fact of not seeking medical attention when pregnancy or delivery complications appear increase the risk of disease and death for the mother and the baby.

Considering the importance of generic care in expecting indigenous Zenu, its necessary for the professional nursing practice to adjust its care actions to the customs and beliefs of this indigenous culture, negotiating, preservating or restructuring them along with the expecting mothers, with the purpose of offering a culturally congruent care (29, 30).

From a cultural perspective, maternity frequently involves beliefs, myths, values and traditional practices that translate in cultural patterns (31). These patterns are generally a product of ancestral traditions that are inherited for generations and their roots are prevalent during the vital cycle of a person. Thus, pregnancy care, as a cultural pattern, involves the family and its surrounded of cultural elements that are supposed to benefit the health of the mother and the baby, with the purpose of preventing complications in both of them (32).

Pregnant women and mothers should be recognized as crucial providers of health and their physical and emotional contributions are essential for the physical and emotional welfare of their children (33). Therefore, Nursing must empower itself in all the care areas and contexts, understanding the needs of the population, being able to provide comprehensive care that recognizes the different existing culture cares.

Knowing the care practices of the pregnant indigenous women vastly contributes to the ethnonursing inputs in the search of actions and programs that contribute to the improvement of perinatal and maternal health of women from different ethnic groups in the county, with the purpose of achieving comprehensive healthcare that is coordinated with the State, the society and their family, This way favoring the purpose of the Comprehensive Healthcare Model (MiAS), particularly in relation to the comprehensive maternal and perinatal healthcare pathways (Resolution 3202/2016 from the Ministry of Healthcare and Social Protection) for expecting mothers from ethnic communities in Colombia, connecting traditional medicine, midwifes and the healthcare system.

Conclusiones

• The culture care practices identified in the pregnant Zenu women evidence an important influence of the cultural traditions and customs of the community. Within the generic care applied by the expecting mothers, there are competent practices for the preservation, negotiation and restructuration by the professional nursing practitioners, such as avoiding heavy lifting, resting often during the day, avoid getting too much sun exposure, avoiding long walks and being comfortable (preserve); avoid having sexual relationships and visiting the midwife (negotiate); base their pregnancy diet on the consumption of fruits, fruit juice and soups and avoid cold (restructure). This way promoting a culturally congruent care offered by nurses that is accepted by the expecting mothers and the community.

• For Zenu women, the main problem that can occur during pregnancy is coldness and its consequences, which seem to appear when the expecting mother does not have the necessary care practices to prevent it, such as showering early, not bathing in wells and bending when urinating in grass. Coldness also brings effects that go from vaginal pain and infections to premature birth and diseases in the mother and the newborn.

• It is important to note that the midwifes are a character from the Zenu ethnic group who have received the ancestral legacy of providing care to the pregnant women in the community. They have great acceptance and credibility from all their community and are in charge of the care of pregnant women during pregnancy and during birth.

• Considering the importance of generic care for the expecting Zenu, and according to the statements from the theory of Leininger, it is necessary that nursing and the health team understand and learn about the generic care of human beings, with the purpose of reaching an agreement that involves their participation, in the interest of offering a culturally congruent care, this way, avoiding cultural differences and favoring the well-being of the people who are provided with comprehensive care.

• The need of promoting special health policies is evident, for the prevention and early detection of pregnancy complications in this kind of community. These policies must be elaborated based on the cultural context, the customs and beliefs of the pregnant indigenous women, also considering their world vision and the generic care they have preserved through time, phenomena that is proper from their culture. This health perspective promotes a maternal and perinatal care adjusted to their culture, which guarantees the prevention and early detection of pregnancy complications, as well as avoiding maternal and perinatal deaths.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare not having any conflict of interest

Bibliographic References

1. Bello Á, Rangel M. La equidad y la exclusión de los pueblos indígenas y afro descendientes de América Latina y el Caribe Santiago de Chile. Rev. CEPAL [Internet]. 2002 [consultado 13 de marzo 2016]. 76:35-54. Disponible en: https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/37960-revista-la-cepal-no76 .

2. Paternina Cruz J. Curiosidades Históricas del Municipio de San Andrés de Sotavento-Córdoba. Volumen II. Barranquilla Corporación Escenarios Proactivos., s.n. editor; 2002.

3. Bodnar Contreras Y. Pueblos indígenas de Colombia: Apuntes sobre la diversidad cultural y la información Sociodemográfica. Bogotá D.C., año 2006. [Trabajo de grado]. Bogotá: Universidad Externado de Colombia. Facultad de Sociología.

4. Resguardo Indígena Zenú Córdoba y Sucre (2008). Cabildo mayor Córdoba y Sucre. Organización política y cultural. Cabildo Mayor Regional del pueblo Zenú, Resguardo Indígena Zenú. San Andrés de Sotavento – Córdoba 2010.

Institución Prestadora de Servicios de Salud Indígena MANEXKA. “Rendición de Cuentas a la Ciudadanía vigencia 2010 “. [Internet]. San Andrés de Sotavento 2010 [Consultado 29 agosto de 2017]. Disponible en: http://manexkaipsi.com/home/

6. Leininger M. Culture Care Diversity and Universality theory and evolution of the Ethnonursing Method. Cap, 1. In: Culture Care Diversity and Universality. Jones and Bartlett Publishers, Sudbury Massachusetts. 2 ed. 2006

7. González Hoyos D. Educar para el cuidado materno perinatal: una propuesta para reflexionar. Rev. Hacia la promoción de la salud [Internet]. 2011 [Consultado 13 de marzo de 2016]; 11:81-93. Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3091/309126325010.pdf

8. Hernández L. La gestación: Proceso de preparación para el nacimiento de su hijo(a). Av. Enferm [Internet]. 2008 [Consultado 25 de junio 2017]; 26(1): 97-102. Disponible en: https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/avenferm/article/view/12889

9. Instituto Colombiano para el Fomento de la Educación Superior ICFES. Investigación Cualitativa Copyright segunda unidad. Bogotá 2006. p. 27.

10. Vera Vélez L. La investigación Cualitativa. Rev. Ponce.Inter.Edu [Internet] 2011 [Consultado 11 de marzo de 2019]. Disponible en: https://ponce.inter.edu/cai/Comite-investigacion/investigacion-cualitativa.html .

11.Spradley J. La entrevista etnográfica. Hardcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers. Orlando Florida: 1979 p. 9.

12. Varguillas Carmona C, Ribot de Flores S. Implicaciones conceptuales y metodológicas en la aplicación de la entrevista en profundidad. Laurus [Internet]. 2007 [Consultado 6 de mayo de 2017]; 13(23):249-62. Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa=76102313 .

13. Vera L. La investigación cualitativa. Rev. UIPR Ponce [Internet] 2010 [Consultado 6 de mayo de 2017]. Disponible en: https://www://ponce.inter.edu/cai/reserva/lvera/investigacióncualitativa.pd .

14. Leininger M. Transcultural Nursing Concepts: Theories, Research & practices Second Edition. College Costom Series, New York. McGraw- Hill; 1995 Chapter 3 p 93-112

15. Tosal B, Richart M, Luque M, Gutierrez L, Pastor R, et al. Signos y síntomas gastrointestinales durante el embarazo y puerperio en una muestra de mujeres españolas. Rev. Atención Primaria [Internet] 2011 [Consultado 21 de marzo de 2017]. Disponible en: http://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-atencionprimaria-27-pdf-S0212656701788968 .

16. República de Colombia. Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social. Resolución 412 de 2000 por la cual se establecen las actividades, procedimientos e intervenciones de demanda inducida y obligatorio cumplimiento y se adoptan las normas técnicas y guías de atención para el desarrollo de las acciones de protección específica y detección temprana y la atención de enfermedades de interés en salud pública. Guía para la detección temprana de las alteraciones del embarazo. [Internet]. Bogotá 2000 [Consultado 9 de agosto de 2017]. Disponible en: http://www.saludcolombia.com/actual/htmlnormas/Res412_00.htm

17. Lattus Olmos J. El determinismo del parto. Rev. Obstet. Ginecol. [Internet]. 2017 [Consultado 21 de marzo de 2017]; 12(2): 103-114. Disponible en: http://www.revistaobgin.cl/articulos/descargar-PDF/754/0716.pdf

18. Vásquez M. El cuidado cultural adecuado: de la investigación a la práctica. En: El arte y la ciencia del cuidado. Grupo de Cuidado Facultad de Enfermería Universidad Nacional. Bogotá: Editorial Unibiblos; 2002. p. 315-322

19. Vásquez Laza C, Ruiz De Cárdenas C. El saber de la partera tradicional del valle del río Cimitarra: Cuidando la vida. Rev. Av. enferm., [Internet].2009 [Consultado 28 de septiembre de 2017]; 27(2):113- 126. Disponible en: https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/avenferm/article/view/12973 .

20. Restrepo Libia J. Médicos y comadronas o el arte de los partos. La ginecología y la obstetricia en Antioquia. Medellín: La Carreta Editores.; 2006.

21. Leininger, MM y McFarland, MR. Enfermería transcultural: conceptos, teorías, investigación y práctica. Nueva York.: McGraw-Hill: 3ª Edición.; 2002.

22. Giraldo Henao C, Orduz Buitrago P. Estado nutricional materno de las mujeres indígenas de Riosucio caldas 2004-2005 y las asociación directa con el peso de sus recién nacidos. Rev. Hacia la promoción de la salud [Internet]. 2007 [Consultado 1 de noviembre de 2016]; 12:193-202. Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/hpsal/v12n1/v12n1a14.pdf

23. Suarez Leal D, Muñoz de Rodríguez L. La condición materna y el ejercicio en la gestación favorecen el bienestar del hijo y el parto. Rev. Av. enferm [Internet].2008 [Consultado 1 de noviembre de 2016]; 26(2): 51-58. Disponible en: https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/avenferm/article/view/12898/13658

24. Lincoln Y, Guba E. Naturalistic inquiri. Rev. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications [Internet]. 1985 [Consultado 25 de junio de 2017]. Disponible en: https://www.colombiamedica.univalle.edu.co/Vol-34No3/ cm34n3a10.htm

25. Medina A, Mayca J. Creencias y costumbres relacionadas con el embarazo, parto y puerperio en comunidades nativas Awajun y Wampis. Rev. Perú. med. exp. Salud pública [Internet]. 2006 [Consultado 27 de febrero de 2018]; 23(1):22-32. Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.pe/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1726-46342006000100004&lng=es

26. Muñoz de Rodríguez L, Vásquez M. Mirando el cuidado cultural desde la óptica de Leininger. Rev. Colombia médica Universidad del Valle [Internet]. 2007 [Consultado 27 de febrero de 2018]; 38(4):98- 104. Disponible en www.scielo.org.co/pdf/cm/v38n4s2/v38n4s2a11.pdf

27. Colliere M. Promover la vida. Madrid.: Mc Graw- Hill Interamericana de España; 1993.

28. Bernal Roldan M, Muñoz De Rodríguez L, Ruiz De Cárdenas C. Significado de sí y de su hijo por nacer en gestantes desplazadas. Rev. Aquichan Universidad de la Sabana [Internet]. 2009 [Consultado 27 de febrero de 2018] 8(1): 97-115. Disponible en: http://aquichan.unisabana.edu.co/index.php/aquichan/article/view/127/255

29. Muñoz Bravo S. Experiencia de la práctica de cuidado transcultural en el área materno perinatal. Rev. Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud Universidad del Cauca [Internet]. 2006 [Consultado junio 30 de 2016]; 8(2):35-37. Disponible en: http://revistas.unicauca.edu.co/index.php/rfcs/article/view/930

30. Montayre J, Sparks T. As I haven’t seen a T-cell, video-str Chávez Álvarez R, Arcaya Moncada M, García Arias G, Surca Rojas T, Infante Contreras M. Rescatando el autocuidado de la salud durante el embarazo, el parto y al recién nacido: representaciones sociales de mujeres de una comunidad nativa en Perú. Rev. Enferm [Internet]. 2007 [Consultado 27 de febrero de 2019]; 16(4):680-7. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-07072007000400012

31. Ruiz J. Prácticas culturales de cuidado en gestantes indígenas de la etnia wayuu: una mirada etnográfica. Carabobo.; República Bolivariana de Venezuela, año 2017. [Tesis de Maestría de Enfermería en Salud Reproductiva]. Carabobo: Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud de la Universidad de Carabobo Venezuela 2017

32. Hernández L. La gestación: proceso de preparación de la mujer para el nacimiento de su hijo. Rev. Av. Enferm [Internet]. 2007 [Consultado 1 de noviembre 2017]; 26(1):97-102. Disponible en: https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/avenferm/article/view/12889/13647

33. Muñoz Henríquez M, Pardo Torres M. Significado de las prácticas de cuidado cultural en gestantes adolescentes de Barranquilla (Colombia). Rev Aquichan [Internet]. 2016 [Consultado 1 de noviembre de 2017] 16(1). Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.5294/aqui.2016.16.1.6

Para citar este artículo / To reference this article / Para citar este artigo/

Ramos Lafont CP, Campos Casarrubia IM, Bula Romero JA. Cultural practices for the care of indigenous pregnant women of the Zenu Reserve Cordoba, Colombia. Rev. cienc. cuidad. 2019; 16(3):8-20

Nurse, Master of Nursing. Professor at the University of Cordoba.

Correo: cpramos@correo.unicordoba.edu.co.

https://orcid.org/0002-9310-1091. Medellín, Colombia.

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8736-9470 Medellín, Colombia.

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0788-0472. Cartagena, Colombia.