Articulo Original

Competence for care and access to rural health

Competencia para el cuidado y acceso a la salud rural

Competência para o atendimento e acesso à saúde rural

Lorena Alejandra Bernal-Barón1

Olga Janneth Gómez-Ramírez2

Abstract

Objective: Describe the competence for the care of the person with chronic disease and their caregiver, residents in rural areas and identify the barriers that limit access to health services. Materials and Methods: A quantitative cross-sectional study, with a non-probabilistic sample of 218 dyads (patient-caregiver), who met the inclusion criteria of the study and to which the following instruments were applied: dyad characterization sheet; Competition for patient and caregiver home care and Survey of access to health services for Colombian homes. Results: The competence for patient care reveals to be lower than that developed by the caregiver. However, in both cases the greatest deficiency in rural residents is the lack of knowledge about the chronic pathology that is suffered, in this way it becomes a challenge for care in rural areas. Likewise, it is evident that access to health services is limited in these populations, due to administrative, economic and displacement barriers to access that are extended by the conditions of the rural area. Faced with this scenario, the nurse becomes the ideal professional and with the adequate capacities to mitigate these difficulties from their actions, through the recognition of the initial conditions of the population and the management of strategies that allow health programs institutions can reach the most vulnerable populations. Conclusion: In rural areas, the challenges are diverse and adverse, however, their intervention is necessary, with the aim of improving health conditions in the populations that reside there.

Keywords:Chronic Disease, Accessibility to Health Services, Rural Population, Caregivers.

Resumen

Objetivos: Describir la competencia para el cuidado de la persona con enfermedad crónica y su cuidador, residentes en zona rural e identificar las barreras que limitan el acceso a los servicios de salud. Materiales y Métodos: Estudio cuantitativo de corte transversal, con una muestra no probabilística de 218 diadas (paciente -cuidador), que cumplieron con los criterios de inclusión del estudio y a la que se aplicaron los siguientes instrumentos: Ficha de caracterización de la diada; Competencia para el cuidado en el hogar paciente y cuidador y Encuesta de acceso a servicios de salud para hogares colombianos. Resultados: La competencia para el cuidado del paciente revela ser menor que la desarrollada por el cuidador. Sin embargo, en ambos casos la mayor deficiencia en los residentes rurales es la falta de conocimientos sobre la patología crónica que se padece, de esta manera se convierte en un reto para el cuidado en la ruralidad. De igual manera, se hace evidente que el acceso a los servicios de salud es limitado en estas poblaciones, dado por barreras de acceso de tipo administrativo, económico y de desplazamiento que se extienden por las condiciones propias de la zona rural. Ante dicho escenario, la enfermera (o) se transforma en el profesional idóneo y con las capacidades adecuadas para mitigar desde su actuar estas dificultades, mediante el reconocimiento de las condiciones iniciales de la población y la gestión de estrategias que permitan que los programas de salud de la instituciones puedan llegar a las poblaciones más vulnerables. Conclusión: En la ruralidad, los retos son diversos y adversos, sin embargo, se hace necesaria su intervención, con el objetivo de mejorar las condiciones de salud en las poblaciones que allí residen.

Palabras Clave: Enfermedad Crónica, Accesibilidad a los Servicios de Salud, Población Rural, Cuidadores.

Resumo

Objetivos: Descrever a competência para o cuidado do doente crônico e de seu cuidador, os residentes rurais e identificar as barreiras que limitam o acesso aos serviços de saúde. Materiais e Métodos: Um estudo quantitativo transversal, com uma amostra não-probabilística de 218 díades (paciente cuidador), que atendeu aos critérios de inclusão do estudo e ao qual foram aplicados os seguintes instrumentos: Cartão de caracterização dos díades; Competência para o atendimento no domicílio do paciente e cuidador e Pesquisa de Acesso aos Serviços de Saúde para domicílios colombianos. Resultados: A competência para o atendimento ao paciente revelou-se inferior à desenvolvida pelo cuidador. Entretanto, em ambos os casos, a maior deficiência dos residentes rurais é a falta de conhecimento sobre a patologia crônica que eles sofrem, tornando-se assim um desafio para o cuidado nas áreas rurais. Da mesma forma, é evidente que o acesso aos serviços de saúde é limitado nessas populações, dadas as barreiras administrativas, econômicas e de deslocamento ao acesso que são disseminadas pelas condições da área rural. Diante deste cenário, a enfermeira torna-se o profissional ideal com as habilidades apropriadas para mitigar estas dificuldades, reconhecendo as condições iniciais da população e gerenciando estratégias que permitem que os programas de saúde das instituições cheguem às populações mais vulneráveis. Conclusão: Nas áreas rurais, os desafios são diversos e adversos; entretanto, sua intervenção é necessária, com o objetivo de melhorar as condições de saúde das populações que nelas residem.

Palavras-chave: Doença crônica, Acessibilidade aos serviços de saúde, população rural, cuidadores

Introducción

The geographical area where people reside influences various aspects of life in which the capacity for care and access to health are not alien to this situation. This is the case of the rural area whose population has been considered in different scenarios, as a population in a vulnerable condition. In rural areas, the conditions that people face are adverse.

In addition to the above, the factors associated with the management of the disease converge and become more complex, which generates that the burden of the disease is greater when the person resides in a rural region (1).

This has repercussions on the health condition of the population, making it more difficult for the patient to care for the disease. Unfortunately, a typical rural population has factors such as low educational level and low socioeconomic status. Associated with these factors, they may also have a history of chronic disease (CD) and advanced age; which are classified as risk factors for worsening CD (2,3). In general, the chronicity of a pathology has repercussions and is at the same time influenced by different aspects of the environment.

It is known that chronic pathology not only impacts the life of the person who suffers it, but also the family dynamics of the patient. Thus, CD is defined as a process of prolonged evolution, which does not resolve spontaneously and rarely achieves a complete cure. CD generates a great social burden both from the economic point of view and from the perspective of social dependency and disability (4). This is how the person with CD who lives in a rural area does not only take care of themselves in health institutions, but also at home with a caregiver. At home, the chronic patient and their caregiver find themselves in a scenario where lack of knowledge and barriers in accessing health services can affect their ability to care.

To measure this capacity, both in the person with CD and in their caregiver, the competence for home care was used, which is defined as the capacity, ability and preparation that the person with CD and / or the family caregiver to carry out the work of caring at home (5). This work is generated from a comprehensive perspective in which aspects of knowledge of the disease, personal conditions, instrumental skills, ability to anticipate, basic factors of well-being and enjoyment, social interaction and support networks are identified (6).

This phenomenon has been widely studied in the national territory, with different populations and varied regions, where the study by Carrillo et al. (5) carried out in the different regions of Colombia, since it is the only study in the country, where a distinction is made between the rural population. However, the lack of studies that deepen this phenomenon in rural areas is evident.

Thus, it is evident that health care and disease do not depend solely on the chronic patient and / or their caregiver, but also that the health system plays an indispensable role from the point of view of access. If the chronic patient has optimal accessibility to health services, he or she will have the opportunity to acquire knowledge, access to medical care and other professionals, the opportunity to receive their pharmacological treatment, among other activities necessary for their watch out.

However, this often becomes a utopia, since what has been experienced is a constant challenge to achieve access to health. It is important to note that the current health system was not designed taking into account the particularities of rural populations and the risks they face (7). The outlook is less encouraging for the most vulnerable populations, such as rural, poor and indigenous populations, since they are the ones with the worst access to health systems (8). Accessibility and care problems tend to be worse in rural areas than in urban areas due to unbalanced economic development and an uneven distribution of health resources (9).

According to the bases of the National Development Plan, barriers and inequities of real and effective access of users to health services still persist. These obstacles are due, among others, to geographical aspects between rural and urban, as well as living in areas with high population dispersion (10). Access to health services in rural areas is a problem in areas like Latin America. This problem has previously been shown to be an important factor related to the quality of assessment of individuals with chronic disorders living in rural and remote areas. (3) Additional health disparities experienced by people living in rural areas such as the Economic inequality, aging populations, transportation problems, and limited health services can have a major impact on how people are able to manage their chronic conditions (1).

At the level of Colombia and according to the national health care quality report, for 2014, the perception of the ease of access to health services was 54%, which indicates that 46% of users considered it difficult access health services (11). On the other hand, according to the Technical Bulletin on Multidimensional Poverty in Colombia in 2018, the percentage of households with barriers to access health services was 6.2% (12). This reflects the existing inequity in health in the country and the felt need to intervene on this topic; Faced with which, investigations have been generated that agree that barriers to accessing health services in Colombia are associated with limited coverage of health insurance, poor income or education, and characteristics of the services such as geographic accessibility, issues administrative or quality (13).

In contrast, from the perspective of the user with CD, care is fragmented, disintegrated and processes difficult, requiring multiple authorizations for different problems related to CD. Family caregivers, who are not prepared to deal with CD, are not considered or supported, increase unnecessary transitions and thus the cost, risk and insecurity of people with CD. Likewise, there are no proposals to adjust to the reality that the country is experiencing in the face of the increase in these diseases and (14) the lack of studies in this regard in rural areas is notorious (7).

In this way, it is evident that access to health services is a fundamental factor for the person with CD and their caregiver to acquire the knowledge, skills and even the support necessary to be competent in caring for the disease. It is necessary in the first instance to identify the problems in order to be able to intervene and modify them. This is how the nurse with an adequate professional and academic level, possesses the capacities to carry out changes in the health status of populations by identifying limitations in the face of access and the lack of tools to face care of the EC. This leads to changes in the way of providing health care and even personalizing it, paying special attention to those populations in a vulnerable condition, including rural populations, since these regions have not only a restricted number of doctors and nurses, but also limited capacity and autonomy to provide the necessary primary health care services (15).

Objectives

• Describe the competence for the care of the person with chronic illness and their caregiver, residents in rural areas.

• Identify the barriers present for access to health services in rural areas.

Materials and Methods

Quantitative, cross-sectional study carried out in the chronic patient care program of a first-level hospital in the municipality of Villa de Leyva, Boyacá (Colombia). The target population of the study were the dyads made up of a person with CD - family caregiver, living in rural areas. The institution's database was used as the sampling frame, which had a total of 500 patients attended by the institution at the time of the study. From this sampling frame, the sample was calculated with a 95% reliability percentage, which resulted in a sample size of 218 dyads. The type of sampling carried out was non-probabilistic, since the application of the instruments was carried out in a face-to-face interview with the participants according to the order of arrival at the sessions scheduled by the institution during the first semester of 2019 and who met the criteria of inclusion.

The study included patients over 18 years of age, with a medical diagnosis of non-communicable CD, where the diagnoses of diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension and chronic kidney disease were included, without neurological or cognitive deterioration. Patients who, despite meeting the inclusion criteria, underwent an acute process of their underlying pathology, without a family caregiver or resident in a geriatric home, were excluded. In the choice of family caregiver, it was taken into account that he or she was over 18 years of age and with a time of more than 3 months in the role of caregiver.

Initially, a pilot test was carried out, in which it was found that the instruments to be used were clear for the participants and that they also made it possible to collect the information necessary for the study. These instruments are the Characterization card of the caregiver-person with chronic disease Diada of the chronic patient care group of the National University of Colombia, which allowed collecting the sociodemographic and clinical identification data of both the patient and the caregiver. The following was the instrument Competence for the care at home of the person with chronic illness / Family caregiver in its short version, through which the individual competence of each component of the dyad was measured. This instrument has a Content Validity Index of 0.97 and a Cronbach's alpha of 0.928. Finally, the Survey of access to health services for Colombian households (EASSS) which has Validation of content and Agreement index> 90%, through this survey, possible barriers to access to health services that could be identified by the dyad.

The recruitment of the participants was carried out during the sessions of attention to patients with CD, programmed by the health institution, during which the main researcher approached the participants through a direct interview where the due diligence of the instruments.

For data processing, an initial database was used where the data were collected and where a rigorous quality control was also carried out in order to reduce possible information biases; then, the IBM SPSS software was used, where the data were processed and measures of central tendency, dispersion and frequencies were calculated for the descriptive analysis. Competency to care at home was analyzed from the high, medium and low stratification levels.

The ethical aspects contemplated in Resolution 008430 of 1993, the ethical principles of Law 911 of 2004 and the guidelines of the Committee of Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) were taken into consideration. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the National University of Colombia and the health institution where the study was carried out, in addition to the above, there was authorization from the respective researchers for the use of the different instruments used in information gathering. Similarly, the informed consent of the participants was obtained, where the minimum risk represented by the study was stated.

Results

Regarding the group of patients, it was found that 78.4% were women, aged between 60 and 74 years, with a minimum age of 31 years and a maximum of 93 years. The main CD found were: arterial hypertension (64.2%), chronic kidney disease (33.1%) and diabetes mellitus (2.8). The time with the disease was 5 to 10 years for 28% and 1 to 5 years for 24.3%. A low educational level was evidenced since 33.9% of the participants had incomplete primary school and 24.3% were illiterate; Regarding marital status, 27.6% were married and 25.7% were widowed; Regarding occupation, 69.3% were dedicated to the home, 56.4% of the subjects belonged to socio-economic stratum 1. Regarding the health insurance system, it was evidenced that 77.5% belonged to the subsidized scheme and 70 , 6% of patients have income below the current legal minimum wage.

The support network provided by the caregivers was also measured, showing that 66.1% of the patients had more than one caregiver. On the other hand, 63.8% did not require daily help. As the main caregiver, a son (a) was identified with 62.8%, however, it is important to recognize that other caregivers were also identified, such as brother, grandson, daughter-in-law, cousin (a), and nephew (a) . Additionally, the patient's self-perceived burden was predominantly low in 69.3% of the subjects.

Regarding the use of ICTs (level of knowledge, access and frequency of use), it was found that the information media such as television (47.2%) and radio (28.8%) are the most used. 77.5% of the patients reported that they did not rely on ICTs to take care of them.

Regarding the group of caregivers, it was found that 70.6% of caregivers were women, with an age between 35 and 59 years, with a minimum age of 18 years and a maximum of 79 years.

Regarding the level of schooling, 21.6% were professional and with a married marital status in 48.6% of the caregivers. Regarding occupation, 34.4% were dedicated to the home, with socioeconomic stratum 1 in 50.0% of the subjects. On the other hand, 51.4% of the caregivers were in charge of the person with CD from the diagnosis of the disease and 53.7% had been a caregiver for between 1 to 5 years. Regarding the perception of the burden, 90.4% consider that they do not present overload due to care.

Regarding the use of ICTs (level of knowledge, access and frequency of use), it was found that the information media such as television (57.8%), radio (38.1%) and the telephone (37 , 2%) are the most used. 78.0% of the caregivers reported that they do not support

They reported that they did not rely on ICTs to take care of their family member.

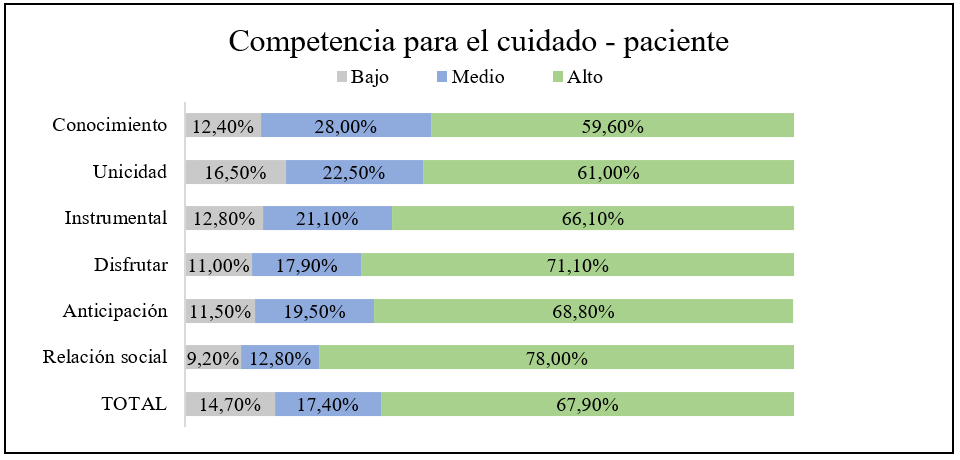

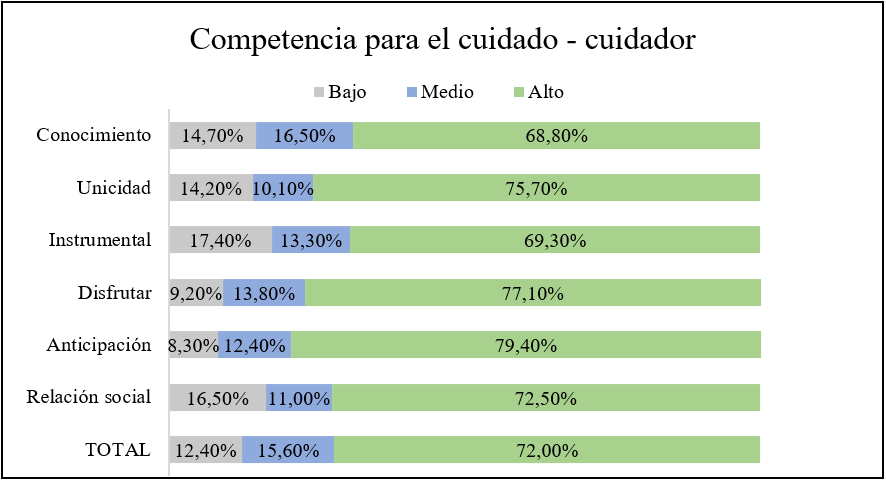

When measuring competence for care in the dyad, the 6 dimensions that comprise it were investigated both in the person with CD (graph 1) and in the family caregiver (graph 2).

Tabla 1: Competence for home care of CD patients in rural areas

Source: Own elaboration.

Tabla 1: Competence for home care of CD patients in rural areas

Source: Own elaboration.

Tabla 1: Competence for care at home of the family caregiver of patients with CD in rural areas

Source: Own elaboration.

Tabla 1: Competence for care at home of the family caregiver of patients with CD in rural areas

Source: Own elaboration.

In general, competence for care was found at a high level in 67.9% of the patients with chronic disease interviewed, in addition, the dimension with the best score was that of social relationship. In the case of family caregivers, competence for care was found at a high level in 72.0% of the caregivers interviewed and for this group the dimension with the best score was anticipation. In addition to the above, it is highlighted that the knowledge dimension was the lowest in both groups.

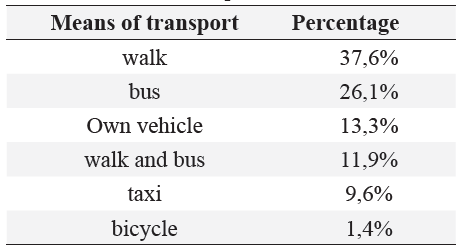

Regarding the access presented by patients with CD residing in rural areas, the access to preventive services was measured, finding that more than 90% of patients attend services such as five-year consultation, taking preventive paraclinics and taking blood pressure. Regarding travel from their place of residence to the health institution, the arrival time in 86.7% of the cases less than 1 hour and 13.3% from 1 to 4 hours. The means of transport used are explained in table 1.

Tabla 1: Means of transport used

Source: Own elaboration.

Tabla 1: Means of transport used

Source: Own elaboration.

Faced with access to curative or rehabilitation services, 23.4% of the patients attended the emergency department, in which cases the time of care was immediate (7.8%), maximum 30 minutes (66.75), between 31 minutes to 1 hour (21.6%) and from 1 to 2 hours (3.9%). Faced with this means of consultation, the patients considered that they received the necessary care (84.3%) and rate the care as very good (19.6%), good (70.6%), and bad (9.8%). The payment of the care was through the EPS subsidized type 86.3% and the contributory type 13.7%.

Compared to the consultation by a general practitioner, 79.8% attended such care, with a 61.5% waiting time for the acquisition of the appointment on the same day. All the patients who consulted, considered that they were offered the necessary care and 95.5% reported not having presented problems in the delivery of treatment. The economic source to cover consultation costs for a general practitioner was EPS subsidized in 70.7%, contributory in 13.8% and special regime in 14.9%. Of the total number of patients who attended a medical consultation, 66.7% were referred to a specialist, of which internal medicine stands out in 29.8% of the cases.

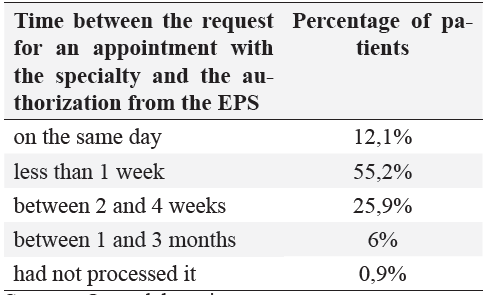

Table 2 shows the waiting time referred by the patients for the authorization of the EPS for the consultation by specialized medicine

Table 2: Waiting times for specialist consultation authorization

Source: Own elaboration.

Table 2: Waiting times for specialist consultation authorization

Source: Own elaboration.

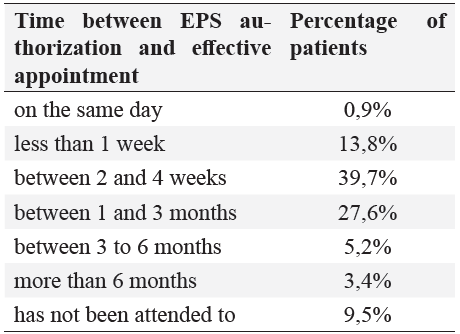

Table 3 shows the waiting time referred by the patients to obtain the effective appointment, after authorization from the EPS.

Tabla 3: Waiting times to obtain a consultation by a specialist

Source: Own elaboration.

Tabla 3: Waiting times to obtain a consultation by a specialist

Source: Own elaboration.

Of the patients who were cared for by a specialist doctor, 85.3% received the necessary care in terms of medication requirements. 94.3% were prescribed medication and in 7.8% of these cases the medications were not delivered, because the medication is not covered by the POS, there were no medications or I did not manage the delivery of these. In general, the patients considered that the quality of care by general and specialist medicine was 26.6% very good, 62.3% good, 9.2% bad and 1.7% did not know does not respond.

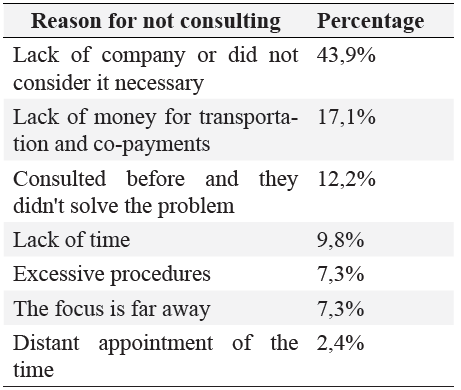

In the case of the patients who did not attend a general medicine consultation, the influencing aspects were varied, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4: Motivos de inasistencia a consulta medica

Source: Own elaboration.

Table 4: Motivos de inasistencia a consulta medica

Source: Own elaboration.

In cases where the doctor was not consulted, 39.0% did nothing, 34.1% used a home remedy, 17.1% self-prescribed, 7.3% used a private doctor and 2.4% went to the healer.

Faced with the need to use hospitalization, 9.6% of the participants required this service with emergency admission, with a time between hospitalization and bed assignment in 47.6% with immediate transfer, 47.6% the same day and 4.8% between 2 to 3 days; the total number of patients who attended said service reported that they received the necessary care in hospitalization; the care received was rated as: very good 19% and good 81%. As a means of payment, 85.7% used subsidized EPS and 14.3% contributory EPS.

Finally, in terms of out-of-pocket expenses, 8.3% of patients must pay a moderating fee or copayment that ranges from $ 3,000 to $ 40,000 (average $ 8,038), 24.8% report having had to pay for exams, medications or procedures that were not delivered or authorized by the EPS ranging from $ 3,000 to $ 500,000 (average $ 87,500). For payment of glasses, hearing aids or orthopedic devices 7.5% required it, with a cost between $ 60,000 to $ 350,000 (average $ 177,500) and finally the extra payment of transportation, accommodation and food required 34.4% with a cost between $ 2,000 to $ 100,000 (average $ 22,400).

Discusión

Responding to the objectives of the study, it was evidenced that the most relevant dimension within the competence for patient care was that of social relationship, in the same way the dimension with the best level of competence in the case of family caregivers was that of anticipation. In general terms, it was observed that about 70% of the dyads are competent in the care of CD. On the other hand, multiple and varied barriers to access to health services were identified in this population; It is worth highlighting the administrative barrier, since it implies a great limitation for the dyads, given the particular characteristics that this population presents. It also becomes a benchmark, since it indirectly involves other barriers such as economic and displacement.

However, it is relevant to go to the review of other variables that may lead to a better interpretation of this study phenomenon, for example, the analysis of the sociodemographic variables of the dyad, where it is highlighted that the majority of people with CD Residents in rural areas, attending chronic patient care programs at the Villa de Leyva ESEo, are women, as in the group of caregivers; These figures are consistent with previous studies, where women play a leading role in both CD and the role of caregiver. A clear example is the study carried out by Carrillo et al (16), where it was evidenced that the highest proportion of CD patients and caregivers were women. A phenomenon that was repeated in the study carried out with caregivers of patients with heart failure in the city of Bogotá (17) and in the same way, in the study by Carreño and Arias (18).

It was also observed that close to 80% of the sample was within the age group of older adults (≥60 years), which can be explained by the aging index that the municipality presents. However, in previous studies such as the one carried out by Aldana et al (19), with patients on hemodialysis, a significant proportion of elderly patients was also evidenced. However, it should be noted that CD is also present in even younger populations, as evidenced in the present study, in correspondence with the study sample measuring competence for care at the national level (16).

Unlike the patient group, a significant percentage of caregivers were between 35 and 59 years

old; values that are related to the findings of the study by Carrillo and Carreño (20), carried out in caregivers of patients with cancer, which ranged from 18 to 53 years. In other words, the majority of family caregivers are located in the economically productive age group, representing a change in role, since, in many cases, they must put aside their jobs to take care of the patient. This results in a direct impact on the economic well-being of the dyad and the need felt by the caregiver for greater financial support from their support network.

Regarding the marital status in the group of patients, although marriage was more common, it was identified that added those states in which the person does not have a partner represent a greater proportion of the sample, which has suggested in other investigations that reduces the ability to care for patients (21). Likewise, the educational level of people with CD in the participating rural area is low, given by a high prevalence of illiteracy and incomplete primary school, thus reflecting the social inequalities typical of rural areas, which have been widely studied.

Thus, the problem of education in the rural world tends to aggravate the difficulties related to the lack of health, because although it is true that the percentage of general illiteracy for Colombia is 8%, this percentage is significantly higher for rural areas (22), as evidenced in the present study in 24.3% of the participants. Likewise, it should be taken into account that the educational level of the population is a determining factor related to health, quality of life, and autonomy in decision-making regarding health care (23). A clear example is the use of ICTs by the dyad, since they did not rely on ICTs to assume care. This situation must be taken into consideration when proposing interventions with the use of ICTs in the rural population. From the use of ICTs, it is possible to improve competence for the care of both the patient and their caregiver, based on the fact that the use of these technologies manages to guarantee the care, coverage and continuity of care and health education in remote or hard-to-reach populations; in addition to improving the communication processes between the patient and the health personnel, offering an alternative to improve their management capacity against the disease and filling those gaps in knowledge regarding the pathology.

It was also evidenced that in general, the study group is located in a low socioeconomic stratum, with low income and affiliation of a subsidized type. This phenomenon is explained by the stagnation of job creation in rural areas, leading to the stabilization of conditions of poverty and inequity. Hence, poverty is 2.3 times higher in highly rural municipalities compared to urban areas. This leads to jobs in informal conditions that prevail in the countryside and therefore to the majority of the rural population being the beneficiary of the subsidized regime (23).

As a whole, the diada has characteristics that increase its condition of vulnerability and likewise the need for intervention, as stated in the national rural health plan created by the Colombian Ministry of Health, where it is intended to prioritize interventions directed towards the aging in order to improve the protection and care of the elderly (24).

Regarding the capacity for care in rural areas, measured through the competence to care for people with CD, it was evidenced that despite the strong difficulties in all areas that this population faces, close to the 60% of the sample obtained an optimal level in terms of their competence for care. However, considering that they are a vulnerable population that also suffers from a chronic pathology, this percentage is not enough. Making the continuous intervention of health personnel necessary, both in monitoring adherence to health programs aimed at this population group and in planning the movement of personnel to areas of difficult access to guarantee the necessary care.

Among the favorable points found in the measurement, an adequate level was observed in the enjoy dimension, which refers to the perception of well-being and quality of life despite the disease. Even though CD is quite limiting, the people with CD who were part of the sample recognize that their quality of life is good. This is closely related to the fact that patients are more competent in the social relationship and interaction dimension, given their ability to relate effectively with their support networks and especially with their primary family caregiver, which contributes to better performance in care work. These dimensions can be favored if, from the nursing role, caregivers are involved in social encounters that allow the strengthening of support networks, as well as the identification of the exhaustion of caregivers who are incompetent in these areas.

Additionally, thanks to the optimal support networks that the patient has and an adequate relationship of care with their caregiver (s), they have developed personal satisfaction from their care and their health condition. Thus, the people with CD interviewed related the acceptance of their pathology to their life process and reported that the spiritual support they receive is of great help when facing their CD. Considering that the Boyacá population has a strong spirituality, this relationship should be expanded in future studies.

Given all the above, it should be noted that despite the favorable proportion of CD patients with a high level of competence for care at home; High points were found such as the uniqueness and knowledge dimensions. This means that participating chronic patients have insufficient basic knowledge about their health condition, as well as about the established medical management that they must follow to reduce the risk of relapses and complications, which leads to a lack of adherence to management doctors.

This phenomenon could be explained from the low educational level of this group. 24.3% of them were illiterate, which leads us to question the effectiveness of the interventions aimed at this population. Educating this population group is especially difficult if it is not characterized in the first instance. In the same way, the limitations already mentioned in rural areas are recognized, such as the small number of health personnel, which reduces the time of intervention in the consultation, which could be dedicated to patient education for the knowledge and recognition of their disease . Faced with this, it is necessary to immerse the nursing staff in the reality of the population, at the same time that the patient must be involved in the structuring of the educational programs generated by the health institution.

In this way, we recognize how the challenges of caring for people with CD in rural areas are based on the felt need for education about their pathology, treatment and possible complications, in order to reduce the catastrophic outcome that pathologies may have. Chronicles on this population and, on the other hand, it is recognized that the educational level affects the ability of the subject to exercise their care.

Regarding the family caregiver, it was identified that he is more competent for the care compared to the patient. This finding is comparable with the investigations that include the dyad, such as the one carried out by Carrillo et al (16), with dyads of family caregivers and person with CD at the national level and in the same way, this difference between the actors of the the dyad, in the study carried out with people with cancer undergoing chemotherapy and their caregivers (6).

Regarding the positive aspects in the care competition, the anticipation and enjoyment dimensions were found. These dimensions refer to the resilience capacity of the caregiver. In this case, it is good, since the quality of life and the personal satisfaction with which it has, measured from the perspective of competence for care, are good, however, it must be borne in mind that these topics may be affected after prolonged development of the role as caregiver. These dimensions are also well represented in studies conducted with caregivers of cancer patients (20).

The dimensions with the lowest levels were knowledge, instrumental and social relationship, that is, the family caregivers in the study present deficiencies in the basic concepts of the disease and, in the same way, reflect low knowledge in the skills of care. This could be related to the low percentage of family caregivers who are in charge of the chronic person since their diagnosis, since time as caregivers improves knowledge and skills in caring (25). Finally, and in contrast to the findings found in the competence of the person with CD, the social relationship dimension is one of the lowest in the group of caregivers, which could be related to what they themselves reported, given the limited support that perceived by other family members when taking care of the person with CD.

Finally, it is recognized that some dimensions must still be strengthened in the dyad, recognizing the particularity of each of its participants, since in the group of people with CD who were part of the research, it is necessary to strengthen what concerns the dimensions knowledge and uniqueness, and on the part of the group of family caregivers the knowledge, instrumental and social relationship dimensions should be promoted.

Given this scenario, the intervention of the nursing professional is necessary and indispensable, since patient education is a fundamental aspect of health care and is increasingly recognized as an essential function in nursing practice (26), which is more than necessary in a community in a vulnerable condition such as the rural area.

In this way, the rural nurse develops a transcendental role in the management of health services and programs, given that it addresses the health process from the analysis and prioritization of the situation to the evaluation and control of health actions ( 27), said process must be based on results of characterization of the rural population, in order to offer more effective and quality care. The nurse should take advantage of their role and recognition within the community, as has been revealed in some studies, since it is evident that people value the advice and opinion of the nurse in the care or recovery of health and is perceived as an instance of trust and support (27).

In this way, the work of the professional in increasing awareness about the health of populations with chronic diseases and high risk, not only helps people to know more about diseases and increase their capacity for self-care, but also helps them to stop unhealthy behaviors and lead a healthy life (28).

The evaluation of the access that the dyad presents to health services was carried out according to different levels: first, access to preventive services, most of which are offered by the E.S.E. first level where they attend their chronic pathology check-ups on a monthly basis, in which a high percentage of adherence is observed, since these services are provided around the chronic check-up consultation they attend monthly. When comparing the findings with the study carried out by Arrivillaga (29) in the municipality of Jamundí, Valle, it was evidenced that those services corresponding to prevention, carried out in health institutions, have a high percentage of adherence.

In contrast, compared to those procedures that the primary care institution does not offer, very low adherence was shown, which is justified by the need for patients to travel to the capital city of the department to take them, which is why they refer not to access them

On the other hand, and as has been widely evidenced in the bibliographic review, the distancing of health centers in the rural population has an important influence on access to services, hence cases were identified in which the dyad had a travel time of even almost 4 hours. Regarding the means of travel used, a large proportion use walking, which, beyond a protective factor for CD, becomes the only resource available to the person with CD and their family caregiver, to gain access to CD. institution; A condition that becomes more complex to perform when the patient with CD is an older adult with mobility limitations.

In addition to the above and taking into account that the dyad has low economic resources, considering the use of a public transport vehicle adds a significant out-of-pocket expense to the dyad, in addition to which, they refer that the transportation system also it is precarious in the municipality, given by the state of the roads, the small number of mobile units and the delay in transfers.

Regarding access to curative services, which include the medical consultation offered by the E.S.E. first level and specialized medical care offered outside the municipality, a high adherence to general medicine appointments was found, given the high supply of the institution; In contrast, in the cases in which the patients did not attend a general medicine consultation, it was found that the aspects that influenced were mainly excessive and costly procedures, poor attention from administrative staff, the care center is far away or lack of money to transportation and copayments. Which again reflects the administrative and economic limitations.

However, the situation with regard to specialized medicine care is not completely different, since the waiting time between the request for the appointment by the general practitioner and the authorization of the same is varied, being between 1 to 4 weeks, arriving even to exceed the month; In addition to the above, this is not the only procedure that this population faces, since after authorization, there is another waiting period between authorization and the achievement of the appointment, which in most cases goes from 2 weeks to 3 months, time in which according to the dyad, the authorizations given by the EPS and / or control paraclinicals that must be delivered for evaluation by the specialist expire, leading to a setback in the process and therefore the need for start the process again, generating delays in the process of patient care and even inadequate care for the current health condition of the same, since the period of time is very long.

It is worth mentioning that specialist care is only provided in the capital city of the department, which adds the displacement from the municipality to the capital city to receive specialized medicine care, representing an additional out-of-pocket expense.

Likewise, in the research by Arrivillaga et al (29), delays were reported regarding the care process by a specialist doctor, especially in the time of authorization by the EPS, where 48.6% took them from 1 day to 1 week; in 36.8% of the sample from 1 to 4 weeks and in 14.7% of cases more than 1 month. Behavior that is repeated when measuring the effective appointment time with the specialist doctor, in which the waiting time between the authorization and the appointment was from 1 day to 1 week in 23.7% of the participants, of 1 to 4 weeks in 52.7% and from 1 to 3 months in 21.8%. Pattern according to what was found in the present investigation, thus showing the administrative barriers caused by the attention of the EPS.

This is a clear reflection of one of the characteristics of the Latin American rural world in which

health services are mainly in urban areas and have very little presence in small populations and in regions with dispersed populations (23). Thus, the challenges faced by this population often refer to access to specialized care and authorizations that delay care.In addition to this, in other investigations, users in rural areas add costs in time and transport , to carry out the process and obtain authorizations (30); thus generating barriers to the population's access to health services, such as administrative and travel barriers.

Similarly, in terms of out-of-pocket spending, which mainly assesses the economic barriers that arise in care, the need for economic contribution in different aspects such as the purchase of medicines was found, this derived from cases where the EPS did not deliver the totality of the prescribed medication, as a consequence of the exclusion of a certain medication in the POS or not having the medication in the ESE first level where the patient is cared for. All this leads to interruptions in medical treatment and even possible abandonment of it. Complementing the above, the diada reported on the requirement of co-payments which are presented in those patients affiliated with the contributory regime.

Finally, expenses in transportation and / or food are the most prevalent in the day, since they are related to the requirement of trips both to the first level institution that provides care in the municipality, as well as to the EPS offices to carry out administrative procedures and also to transfer to the capital city of the department, to receive specialized medical attention or receipt of medicines that are not delivered at the reference care center. By associating these expenses with the economic conditions of the dyad, it is recognized that the obligation of these payments becomes an important barrier to access to health services.

From this point of view and given that rurality constitutes an important risk factor for access to services, providing comprehensive and continuous care from a cultural perspective, considering that in rural areas there are multiple forms of traditional cultural care, it is a primary task In addition to being recognized as having the ability to solve problems in situ in a timely and efficient manner in order to manage the population's access to the healthcare network (27). Providing information on these phenomena from the perspective of patients and their caregivers, offers a broad vision to the nursing professional, of the felt need for an intervention far beyond the institutional obligation, since it implies making use of the knowledge that is had about the special conditions of the population to intervene; In addition to knowing its own limitations. It allows to reinvent the care that the nurse offers, in order to correct to some extent, the deficiencies identifiable from the information provided by the users of the system on health problems, even they themselves can reach offer solutions through teamwork with the same staff who serve them.

However, the obvious limitations that the nurse has, which go beyond their task, cannot be denied, since to minimize or completely eliminate barriers to access to health services, a intersectoral work, which includes the central axes that direct and manage the health system itself.

Therefore, the nurse becomes, on many occasions, the link between the communities and the health institutions, and at the same time has the possibility of making visible the access conditions that patients are faced with. In this way, their recognition of the needs of others becomes a practical tool when leading the necessary modifications in rural areas, in the face of community health care. Thus, the nurse safeguards the right to health in one way or another and is obliged to promote change initiatives in front of the same health team and in different instances in order to achieve a positive impact on care and care of the rural chronically ill.

In conclusion, the identification of access barriers to health services in rural areas is fundamental since it allows public policy makers and directors of municipal programs to detect where the main access limitations are; in order to establish the pertinent corrections to guarantee the use of health services in a timely manner, facilitating health care for the population.

In addition, it allows to contribute knowledge from the perspective of the users of the system, on the aspects that determine the access, since the studies that deepen in this topic are scarce (31).

Conclusions

• The main challenge to be faced by the care of the disease in the rural area, by the patient with CD and his or her caregiver, is the limited knowledge they have to deal with the chronic disease and the living conditions that make it difficult to obtain these.

• In spite of the different limitations generated in rural areas, the nursing professional has a very useful tool to generate change in the face of the challenges revealed in the deficiencies of competence for the care of patients with CD and their caregivers, education; since their leadership is recognized by different actors in the area of community education, and at the same time they have the facility of constant contact with both individuals and communities.

• The challenges faced by the rural dyad in terms of access to health services derive from the barriers to access, among which are those identified in the study that were administrative, economic and displacement barriers.

• The nurse in rural areas is indispensable when it comes to identifying the existing challenges in the process of caring for chronic diseases and at the same time in the access to services for people who suffer from these pathologies, recognizing the professional as the ideal entity to generate processes of change.

• Given the type of attention offered to the dyads, it is very useful to make use of the care programs for people with CD, in order to strengthen especially the deficient knowledge that the dyad has, which will improve in important measure its competence to care. Similarly, when considering the use of ICTs, comprehensive pedagogical approaches should be taken into account to ensure care that is more appropriate to social and cultural contexts.

Conflict of Interest

Los autores declaran no tener ningun conflicto de intereses.

Referencias bibliográficas

1.Goeres LM, Gille A, Furuno JP, Erten-Lyons D, Hartung DM, Calvert JF, et al. Rural-Urban Differences in Chronic Disease and Drug Utilization in Older Oregonians. J Rural Health [Internet]. 2016 [Consultado 30 enero 2020];32(3):269–79. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12153

2.Lauckner HM, Hutchinson SL. Peer support for people with chronic conditions in rural areas: a scoping review. Rural Remote Health [Internet]. 2016 [Consultado 25 enero 2020];16(1):3601. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26943760/

3.Paskulin LMG, Molzahn A. Quality of Life of Older Adults in Canada and Brazil. West J Nurs Res [Internet]. 2007 [Consultado 22 marzo 2020]; 29(1):10–26. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0193945906292550

4.Hayter AKM, Jeffery R, Sharma C, Prost A, Kinra S. Community perceptions of health and chronic disease in South Indian rural transitional communities: a qualitative study. Glob Health Action [Internet]. 2015 [Consultado 22 marzo 2020]; 8(1):25946. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v8.25946

5.Carrillo-González GM, Barreto RV, Arboleda LB, Gutierrez-Lesmes OA, Gregoria-Melo B, Tamara-Ortiz V. Competencia para cuidar en el hogar de personas con enfermedad crónica y sus cuidadores en Colombia. Rev la Fac Med. 2015;63(4):669–75.

6.Sánchez LM, Mabel Carrillo G. Competencia para el cuidado en el hogar diada persona con cáncer en quimioterapia-cuidador familiar. Psicooncologia. 2017;14(1):137–48.

7. Quintero D. Patricia S. Sobre una propuesta de popularización del derecho a la salud con comunidades rurales 1. A proposal about the popularization to the right of health with rural communities. 2016;12.

8.Bejarano-Daza JE, Hernández-Losada DF. Fallas del mercado de salud colombiano. Rev la Fac Med [Internet]. 2017 [Consultado 22 noviembre 2019]; 65(1):107–13. Available from: https://doi.org/10.15446/revfacmed.v65n1.57454

9. Huang X, Yang H, Wang H, Qiu Y, Lai X, Zhou Z, et al. The Association Between Physical Activity, Mental Status, and Social and Family Support with Five Major Non-Communicable Chronic Diseases Among Elderly People: A Cross-Sectional Study of a Rural Population in Southern China. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2015 [Consultado 22 noviembre 2019];12(12):13209–23. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph121013209

10. Casado-Cañete F. Objetivos de desarrollo del milenio. Informe Universidad Politecninca de Catalunya, Epaña [Internet]. 2015 [Consultado 22 noviembre 2019]; 56-57. Available from: https://upcommons.upc.edu/handle/2099/7274

11.Informe nacional de calidad de la atención en salud 2015. Ministerio de salud y protección social Colombia. 2015. Available from: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/DE/DIJ/informe-nal-calidad-atencion-salud-2015.pdf

12. Boletín Técnico de Pobreza Multidimensional en Colombia Año 2018. DANE. Available from: https://www.dane.gov.co/files/investigaciones/condiciones_vida/pobreza/2018/bt_pobreza_multidimensional_18.pdf

13.Restrepo-Zea JH, Silva-Maya C, Andrade-Rivas F, Vh-Dover R. Acceso a servicios de salud: Analisis de barreras y estrategias en el caso de Medellin, Colombia. Rev Gerenc y Polit Salud. 2014;13(27):236–59.

14.Maimela E, Alberts M, Modjadji SEP, Choma SSR, Dikotope SA, Ntuli TS, et al. The Prevalence and Determinants of Chronic Non-Communicable Disease Risk Factors amongst Adults in the Dikgale Health Demographic and Surveillance System (HDSS) Site, Limpopo Province of South Africa. PLoS One [Internet]. 2016 [Consultado 22 noviembre 2019];11(2):e0147926. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0147926

15.Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Ampliación del rol de las enfermeras y enfermeros en la atención primaria de salud. Washington, D.C.: OPS; 2018.

16.Carrillo-González GM, Barreto-Osorio RV, Arboleda LB. Competencia para cuidar en el hogar de personas con enfermedad crónica y sus cuidadores en Colombia. Bogota, Rev. Fac. Med. 2015 Vol. 63 No. 4: 665-75

17. Achury-Saldaña DM , Restrepo-Sánchez A , Torres- Castro NM, Buitrago-Mora AL, Neira-Beltrán NX , Devia-Florez PD. Competencia de los cuidadores familiares para cuidar a los pacientes con falla cardíaca. Rev Cuid. 2017; 8(3): 1721-32.

18. Carreño-Moreno S, Arias-Rojas M. Competencia para cuidar en el hogar y sobrecarga en el cuidador del niño con cáncer. Gac Mex Oncol. 2016; 15(6):336–43.

19.Aldana EA, Barrera SY, Rodríguez KA, Gómez OJ, Carrillo GM. Competencia para el cuidado (CUIDAR) en el hogar de personas con enfermedad renal crónica en hemodiálisis. Enfermería Nefrológica [Internet]. 2016 [Consultado 22 noviembre 2019];19(3):3–9. Available from: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2254-28842016000300009&lang=pt

20.Carrillo GM, Carreño SP, Sánchez LM. Competencia para el cuidado en el hogar y carga en cuidadores familiares de adultos y niños con cáncer. Revista Investigaciones Andina. 2018; 20(36):87-101.

21.Girardi-Paskulin LM, Molzahn A. Quality of Life of Older Adults in Canada and Brazil. West J Nurs Res [Internet]. 2007 [Consultado 22 marzo 2020]; 29(1):10–26. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0193945906292550

22.Pérez-Correa E. Nueva ruralidad, globalizacion y salud. Rev CES Med 2007; 21(Supl 1):89-100

23.Pineda BC. Desarrollo humano y desigualdades en salud en la población rural en Colombia. Univ Odontol. 2012 Ene-Jun; 31(66): 97-102.

24.Republica de Colombia. Plan Nacional de Salud Rural Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social [Internet] 2018; Available from: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/DE/PES/msps-plan-nacional-salud-rural-2018.pdf

25. Coppetti LC, Girardon-Perlini NMO, Andolhe R, Gutiérrez MGR, Dapper SN, Siqueira FD. Caring ability of family caregivers of patients on cancer treatment: associated factors. Rev. Latino-Am. Enfermagem. 2018; 26:e3048.

26. Soto P, Masalan P, Barrios S. La educación en salud, un elemento central del cuidado de enfermería. ELSEVIER. 2018; 29 (3):288-300.

27.Marilaf M, Alarcón A, Illesca M. Rol del enfermero/a rural en la región de la Araucanía Chile: percepción de usuarios y enfermeros. Ciencia y Enfermería. 2011 (2):111-118.

28.Tian M, Wang H, Tong X, Zhu K, Zhang X, Chen X. Essential public health services’ accessibility and its determinants among adults with chronic diseases in China. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):1–12.

29.Arrivillaga M, Aristizabal JC, Pérez M, Estrada VE. Encuesta de acceso a servicios de salud para hogares colombianos. Gac Sanit [Internet]. 2016; 30(6):415–20. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2016.05.008

30.Campaz N, Montaño SM. Barreras de acceso al servicio de salud en el contexto colombiano a partir de la promulgación del derecho a la salud en la legislación colombiana. Universidad Santiago de Cali; 2019.

31. Acosta SR. Barreras y Determinantes del Acceso a los Servicios de Salud en Colombia. [Tesis Especialización]. Popayán: Universidad EAN - Universidad del Cauca; 2010.

Para citar este artículo / To reference this article / Para citar este artigo/

Bernal-Barón LA, Gómez-Ramírez OJ. Competence for care and access to rural health. Rev. cienc. cuidad. 2020; 17(3):46-60 https://doi.org/10.22463/17949831.2210

0000-0002-5807-3208.

00000-0002-9160-4170.